Mississippi Museum of Art Gwen Magee Our New Day Begun

Fig. i. View of Natchez past John James Audubon (1785–1851), 1823. Oil on sail, 29 ⅜ past 48 ⅜ inches. Greenville County Museum of Art, South Carolina, purchase, with funds from the 2010 Museum Antiques Show, sponsored by Carolina Start Chairman'southward Circle.

Whoever remarked that Mississippi is "America, only worse" might amend that quip if they'd been to Jackson with me recently—especially if they'd gone from the city's stupendously successful new Mississippi Civil Rights Museum to the Mississippi Museum of Art's exhibition Picturing Mississippi. What the Ceremonious Rights Museum does so vividly for the twentieth century's dramatic decades of protest is deepened at the MMA with approximately 175 works of art that bring the state's pictorial by to the electric current moment and by doing so indicate a manner forward—and not just for the arts. This vivid gathering of images and objects from the eighteenth century to the present is arranged with a certain deadpan ease that gives didacticism a good proper noun: the galleries of historical fabric are punctuated with the work of contemporary artists who have met the high toll of history with spirited, imaginative work. Picturing Mississippi has a subtitle—Land of Plenty, Pain, and Promise. They aren't simply bravado smoke with that last fleck of ingemination.

Fig. ii. Delia, attributed to James Reid Lambdin (1807–1889), c. 1850. Oil on sheet, 35 by 25 ½ inches. Collection of Sarah Lawrence Oakes.

Fig. 4. Portrait of John Police by Willem Verelst (1704–1752), 1727. Oil on canvas, 49 ½ by 39 ¾ inches. Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art, St. Louis, Missouri, buy, with funds donated by the Enid & Crosby Kemper Foundation.

The Mississippi Museum of Art is not a state museum. From its ancestry in 1911 every bit the Mississippi Art Association, information technology has ever had a high degree of local date combined with cosmopolitan sense of taste. Both come up into play in the works called and the mode they are presented in Picturing Mississippi. I was interested to come across the exhibition'due south chief curator, Jochen Wierich, and find that he was born and raised in Federal republic of germany, before coming hither to explore and celebrate our fine art. Where would nosotros be, I found myself wondering, without people like Wierich, who often seem to know us better and like usa more than we similar ourselves? I'm sure he is here considering the museum's savvy managing director, Betsy Bradley, knows the answer to that question.

There has been a lot of inventive programming surrounding the exhibition— films, symposiums, music—much of it under the banner of CAPE, the museum's Center for Fine art and Public Exchange. CAPE'due south director, Julian Rankin, seems improbably young to have an important book forthcoming on Ed Scott Jr., a sharecropper'southward son who became a Mississippi entrepreneur, but there are plenty of other surprises downward here. The exhibition ends with one of them: a room that is non part of the prove merely makes a stunning coda. Thomas Sayre's 2016 White Gilded, a huge installation of globe-cast sculptures and two panoramas—40 feet and fifty-six feet long—that are nigh frightening in their oppressive evocation of Rex Cotton and the earth information technology comes from. White Gold originated at the Contemporary Art Museum in Raleigh, North Carolina. Bringing it hither must accept been a pregnant undertaking—another example of the energy and courage you don't often detect in many wealthier museums.

Fig. 3. Route to Shubuta by Noah Saterstrom (1974–), 2016. Oil on canvas, 48 by 96 inches. Collection of the creative person.

To assemble Picturing Mississippi, the organizers added to the museum's holdings by borrowing from no fewer than lxx-ane museums, galleries, and private collections. What, exactly, were they afterward? My guess is that they wanted to show non only what the by looked similar but how information technology looks to united states today, and to get from there to what our gimmicky gaze may hold for the future. To begin near the beginning—and the show is chronological up to a betoken—1 gallery offers early depictions of Natchez, the antebellum South's showplace, with all its contradictions subtly in place: portraits of prosperous citizens, a fascinating Natchez landscape by John James Audubon (Fig. one), an engraving after a drawing by Henry Inman of the enslaved prince Abdul Rahman Ibrahima, and one of a female slave attributed to James Reid Lambdin (Fig. 2), more familiar equally a painter of presidential portraits. In that location is likewise something else: Noah Saterstrom'due south 2016 Road to Shubuta, an ironic panorama of another town with a grisly racial past past a contemporary artist who grew upward in Natchez (Fig. 3).

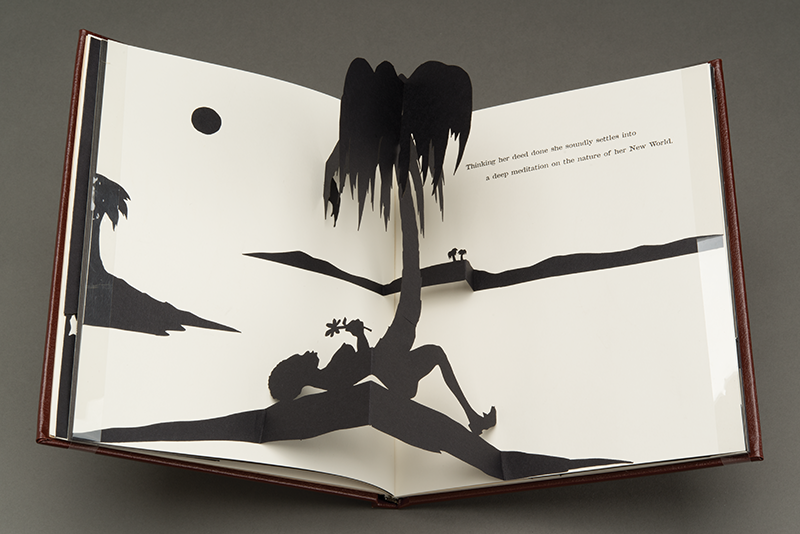

Fig. 7. Liberty: A Fable (A Curious Estimation of the Wit of a Negress in Troubled Times) by Kara Walker (1969–), 1997. Leather-bound volume of get-go lithographs and five laser-cut, pop-up silhouettes on wove newspaper; ix ⅜ by 8 ⅜ inches (closed). Mississippi Museum of Fine art, souvenir of R. Andrew Maass; photo © Kara Walker, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

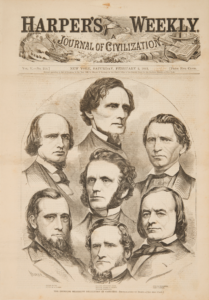

Fig. 5. The Seceding Mississippi Delegation in Congressby Winslow Homer (1836–1910), after photographs past Mathew B. Brady (1823–1896), comprehend of Harper's Weekly, February two, 1861. Signed "homer" at lower left. Wood engraving, 15 ⅝ by 10 ⅞ inches. Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson.

Fig. 6. Mó-sho-la-túb-bee, He Who Puts Out and Kills, Chief of the Tribe by George Catlin (1796–1872), 1834. Oil on canvas, 29 by 24 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison Jr.

Elsewhere, just every bit we are absorbing the story of the land and its commencement inhabitants as depicted past George Catlin (Fig. 6) and others, we see the portrait of a bewigged foreign fat cat in first-class silk and satin (Fig. 4). What is he doing here? The reply to that question demonstrates the lengths to which the curatorial team has gone to tell this story. The 1727 portrait past Willem Verelst depicts John Law, a Scottish banker who encouraged European investors to speculate on the wealth to be gleaned from the land. That speculation eventually turned territory into property, setting the stage for the removal of the tribes. This portrait, unknown until the 1970s, and caused past the Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art in St. Joseph, Missouri, languished until it could take this moment in the visual history of Mississippi.

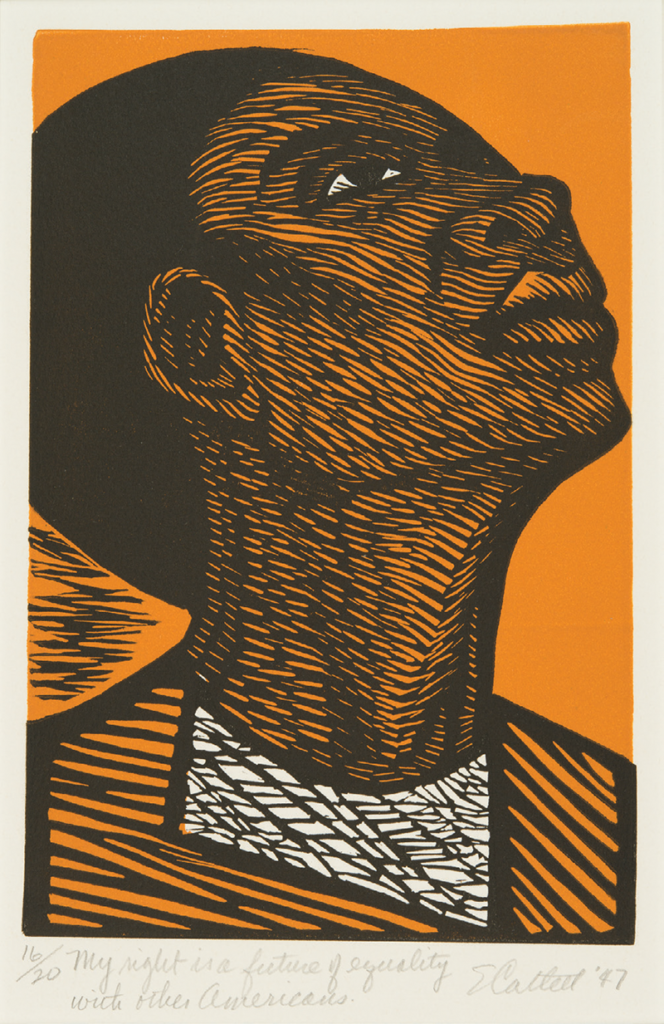

Fig. eight. My Correct Is a Future of Equality with Other Americans byElizabeth Catlett (1915–2012), from The Negro Woman series, 1947. Numbered "16/xx" at lower left; inscribed "My correct is a future of equality with other Americans." at lower center; signed and dated "ECatlett '47" at lower right. Linocut, ix ⅛ by half dozen ⅛ inches. Mississippi Museum of Art, gift of the artist.

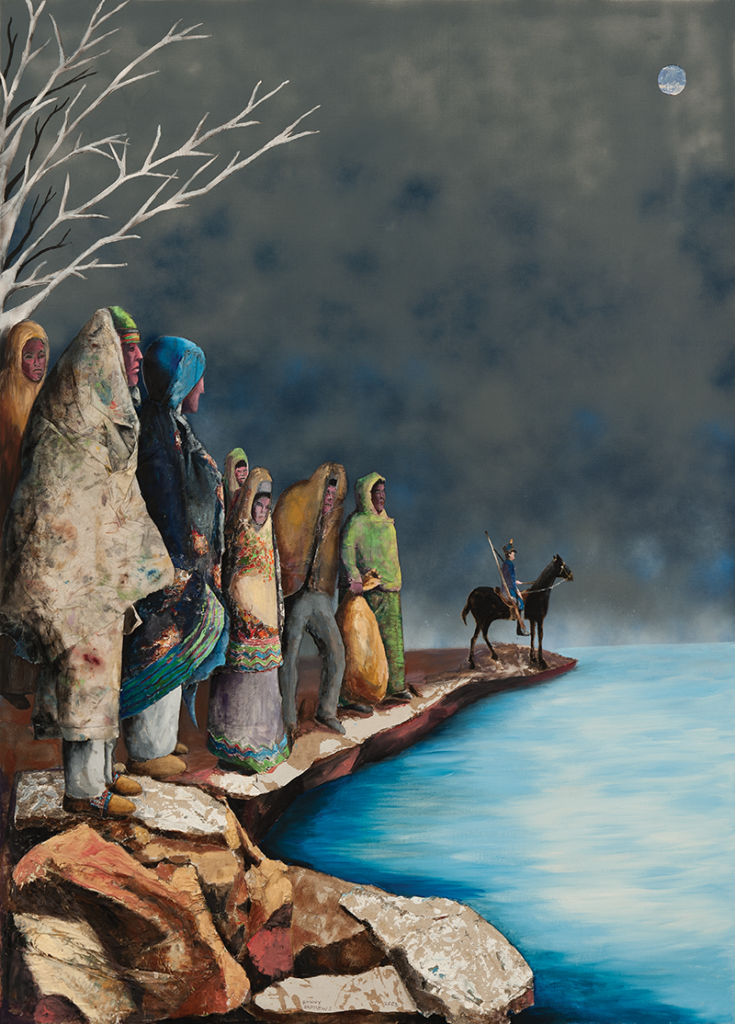

At the other end of history in this gallery nosotros find Mississippi River Bank, a piece of work from Benny Andrews's 2005 Trail of Tears series (Fig. 12). His tribal figures don't wait then much poised for exile as teetering on the edge of extinction. History lives . . . but they don't need to say that here.

The treatment of the Confederacy and the Civil War is no less pungent. For the most function, the war is delivered as it was at the fourth dimension past illustrations from Northern artists such equally Winslow Homer for Harper's Weekly and other publications (see Fig. 5). The one triumphant rebel yell comes from William D. Washington's painting of Stonewall Jackson'due south arrival in Winchester, Virginia. Just there is something else going on as well: numerous depictions of the slave trade and of slavery throughout the exhibition have kept the focus both implicitly and explicitly on the state's half million enslaved souls; the postwar notation of Lost Cause galantry you lot might have expected is not sounded.

Fig. ten. Anxiety of Negro Cotton hoer near Clarksdale, Mississippi by Dorothea Lange (1895–1965), 1937. Reproduction from digital file of original negative, x ½ by 14 inches. Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Prints and Photographs Division.

Instead, reflection on the aftermath of the Civil War comes from our contemporary Kara Walker. Liberty: A Fable (Fig. seven), her bound book with five laser-cut pop-upwardly silhouettes, tells the story of an emancipated slave who constitute that her liberty was illusory. Like other contemporary works in the exhibition, Walker's is and then vigorous and so original that its very existence pushes the states beyond the bleakness of its message. As Ta-Nehisi Coates has implored artists to do, it turns protest into production.

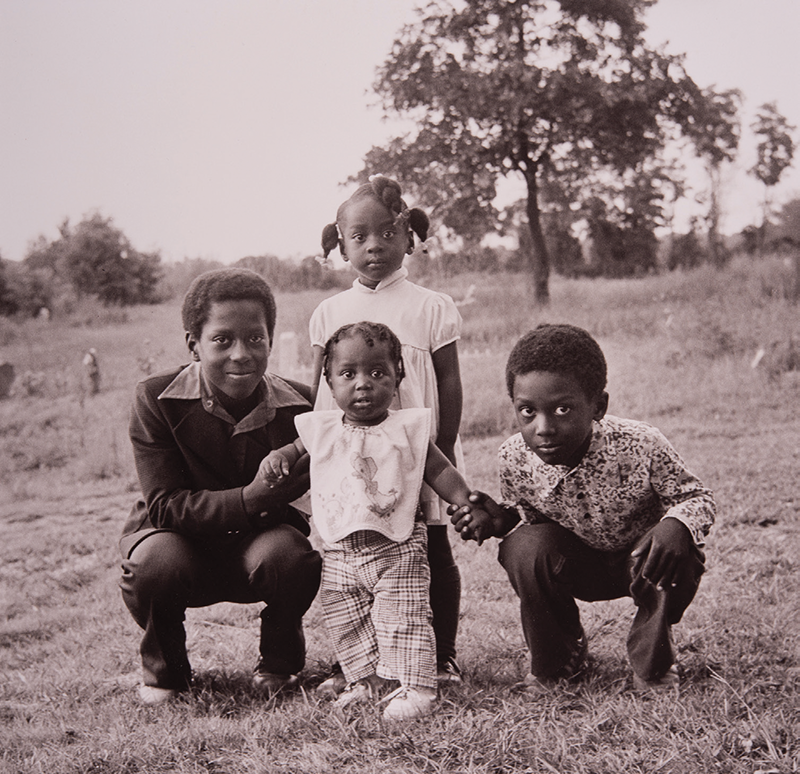

Fig. 9. Untitled photograph from the Mississippi Portfolio past James Perry Walker (1945–2014), c. 1975. Gelatin silvery impress, 17 inches square. Mississippi Museum of Fine art, buy with funds from Mary Mhoon Endowment.

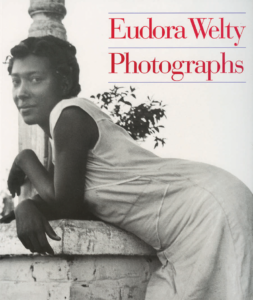

And and then it goes until we get to the Depression and the indelible WPA and Farm Security Administration photographs of the downtrodden by Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange (Fig. 10), Ben Shahn, and others. To these the museum has added photographs by Eudora Welty, the Jackson novelist and short story writer who was on consignment for… Eudora Welty. Her camera captures people and scenes with a broader sense of Mississippi life than the piece of work of the nifty photographers down at that place on a visit. I wish the museum had been able to include 1 more of her shots: the i that appears on the cover of her book Eudora Welty: Photographs (Fig. 13). It speaks so eloquently of a sure unexpected optimism, a theme the exhibition is pursuing.

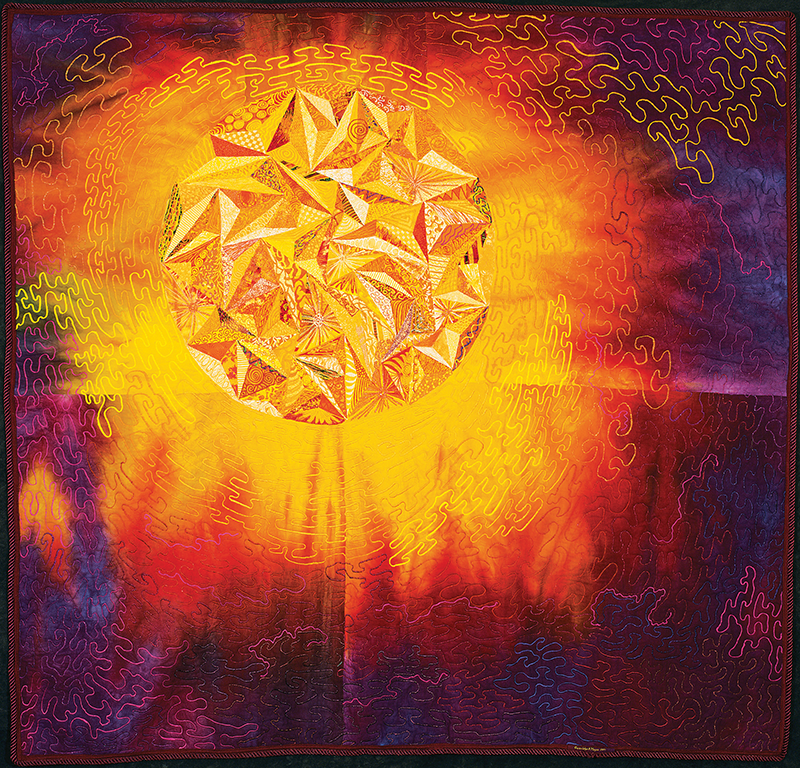

Fig. 11. Our New Twenty-four hour period Begun, quilt by Gwendolyn A. Magee (1943–2011), 2000. 70 ½ by 73 ¼ inches. Estate of Gwendolyn A. Magee, New Orleans, Louisiana.

There is much more—from the civil rights motility to the present 24-hour interval, explored in images both celebrated and contemporary. Bruce Davidson's photographs of the Freedom Riders are hither and so is Sam Gilliam's 1970 draped canvass, Cerise Apr, a chilling evocation of the blood of Martin Luther King Jr. McArthur Binion'southward 2015 Dna—a coded work in which the artist's Mississippi birth document, identifying him every bit "colored," is covered in intricate grids of oil stick—hangs not that far from a much earlier piece of work, a 1790–1791 painting of the transatlantic slave trade.

Fig. 12. Mississippi River Depository financial institution past Benny Andrews (1930–2006), from the Trail of Tears series, 2005. Signed "benny/andrews" and dated "2005" at lower center. Oil on sail with painted fabric collage, 70 by 50 ½ inches. © Manor of Benny Andrews, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

And and so there is Our New Mean solar day Begun (Fig. 11), i of Gwendolyn Magee's extraordinary quilts, its title taken from a line in "Elevator Every Voice and Sing," the unofficial African-American anthem and the inspiration for Magee's twelve-quilt serial of that proper name. Unlike other quilts in the series, which depict the darker fabric of chain gangs and lynchings, Our New 24-hour interval bursts along in colour, leaving no doubt that at that place is a road alee. It is the last slice in the exhibition.

Fig. 13. Cover of Eudora Welty: Photographs (University Press of Mississippi, 1989).

And that brings the states to At present: The Telephone call and Expect of Liberty at the Tougaloo College Fine art Gallery, some ten miles due north of Jackson. The eighteen works on view are drawn in part from the MMA, in role from Tougaloo's impressive collection, plus 4 that were borrowed by the exhibition's curator, La Tanya Autry, who is also a curator at MMA. I first became aware of Autry when I went to see her exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery of Lee Friedlander's lilliputian-known photographs of the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Liberty. I was impressed then by her insistence that freedom must be more than protest, that it needs to be represented by works of art that prove what it can look similar in ordinary life. That is, in office, the Now in this exhibition's title: people going about their business, doing ordinary things. And so this small-scale only important gathering of works rings the freedom bong with art by Elizabeth Catlett (Fig. viii), Romare Bearden, and Betye Saar, and with James Perry Walker'southward image of four kids posing for a family unit photo (Fig. ix).

What Autry and the Mississippi Museum of Art practice side by side is something we should all look forward to.

Picturing Mississippi, 1817–2017: State of Enough, Pain, and Hope is on view at the Mississippi Museum of Art through July eight.

At present: The Call and Look of Liberty is on view at the Tougaloo College Art Gallery through May 15.

Jackson: Five dining recommendations

Owner of Groovy'south Eating house, Ballery Tyrone Bully, with his wife, Greta Brown, and their girl Tyrea. Photograph by Kimber Thomas; courtesy of the Southern Foodways Alliance.

If you lot go to Jackson to visit its three great museums—and you should—in that location are expert places to stay and expert things to eat. I went to Bully's, a tiny soul food spot where they care for yous like family. Information technology was Feb 28 and the place was packed at lunchtime. Equally I waited for my ribs and blackeyed peas, the crowd stood to sing "Lift Every Vocalism and Sing" and I realized it was the last twenty-four hours of Black History Month. – E.P.

Betsy Bradley, Director, Mississippi Museum of Art

I love taking guests to Parlor Market in downtown Jackson. The warm atmosphere and open kitchen interruption downwards all kinds of barriers between customers

and kitchen staff. Chaz Lindsay, the chef, creates astonishing homemade pastas that ship one'south imagination straight to Italy. And the eatery is co-owned past a vivid chef who has iv great restaurants throughout the city. You can't become wrong in one of Derek Emerson'due south Jackson eateries.

Jochen Wierich, Interim Chief Curator

There are 2 hotels downtown that serve groovy food. When I start came to visit Jackson, I e'er stayed at the Hilton Garden Inn (besides known by its old proper noun: the Rex Edward Hotel) and ofttimes ate at the restaurant. I would normally starting time off with a cup of gumbo, which is excellent, and and then club a seafood dish. I liked their grilled shrimp with some grits on the side, and I very much enjoyed the carmine fish plate. I also ate at the bar and treated myself to a fantastic margarita. The other restaurant I like is Estelle's inside the Westin hotel. They serve delicious salads.

La Tanya Autry, Curator of Art and Civil Rights

I happen to dearest La Brioche's turkey with brie and preserves on a baguette with the mixed greens side. I know that doesn't match a lot of people'due south idea of Southern cuisine, but when I was an undergraduate, I studied in the due south of France. There are all kinds of southern. La Brioche's sandwich

reminds me of bon temps in Avignon!

Julian Rankin, Managing Director, Center for Art & Public Exchange

For an immersive Mississippi culinary experience, I tell pilgrims to visit Hal and Mal's, a downtown Jackson anchor. The edifice is a historical

certificate, the Southern and Creole recipes are handed downward through the generations, and the musical history caulks the brick. 1 of the titular founding brothers is Mississippi Arts Commission Executive Director Malcolm White, who has long fueled arts and music in the state.

collinsandishishe.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/breaking-new-ground/

Post a Comment for "Mississippi Museum of Art Gwen Magee Our New Day Begun"